Factsheet – When will I go into labour?

Frances Tervet

Midwife and neonatal nurse

@francestervet

Summary

You’ve been given an Estimated Due Date (EDD) and have been looking forward to that magical day for months. However, very few babies actually do arrive on their due date. But when will you go into labour?

This factsheet provides information surrounding the ‘mythical’ due date and looks at how normal it is for pregnancy to extend past this date. A full term pregnancy describes a pregnancy that is between 37 and 42 weeks; the due date is just one day in the middle of that. Going into labour can present itself in different ways for different people and this factsheet will provide you with common signs that labour is on the way or has indeed started and when to contact your care professional.

There are many old wives’ tales surrounding pregnancy and birth; some of which we now know to be potentially harmful. This factsheet provides current evidence-based information with regards to fetal movements and maternal movement and positioning in the latter stages of pregnancy.

This factsheet will provide you with practical advice and information when approaching the end your pregnancy and awaiting the birth of your baby.

What we know

Labour is thought of in three separate stages: the first, second and third stage1. At the start of labour, the first stage, the cervix (neck of the womb) begins to soften so that it can begin to open (dilate). Established labour is when the cervix has opened to 4cm and the contractions are more regular in length and intensity2. These contractions cause the baby’s head to press down on the cervix, which causes it to dilate further3. When the cervix has dilated to 10cm, the baby’s head can begin to descend through the birth canal and your body begins to push the baby out. This is known as the second stage of labour4. The time after the baby is born until the placenta is delivered is known as the third stage.

Often, in the third trimester of pregnancy, you may feel tightenings of the muscles in the uterus. These are known as Braxton Hicks and are ‘warm-up’ contractions for labour5. They can be quite sporadic and are irregular in duration and intensity, unlike contractions in true labour4. These are a normal part of pregnancy4,5 and they may be very noticeable and uncomfortable at times. However, some women report hardly noticing them at all. Braxton Hicks can turn into established labour so it is important to call your care provider if you think you are in labour. Your midwife will have provided information so that you know when to call.

Another sign of changes in the body and within the cervix is the loosening of the mucus plug. During pregnancy, the cervix is ‘plugged’ with a jelly, mucus-y substance, known as the mucus plug6. It sits within the cervix and serves to block out any potential infections and to maintain the womb as a sealed, secure and sterile unit6. As the cervix softens or changes shape before or during labour, the mucus plug is released. The mucus may be tinged with brown, pink or red blood and is often called a ‘bloody show”7 [Image 1]. Some women notice this before they go into labour but for other women it won’t come away until labour has commenced. It is a good indicator that labour is on its way but does not provide any exact timescale.

Image 1

According to research, only about 4% of babies are born on their due date8,9. Most babies are born between 37-41 weeks9,10 but your due date is only an estimate of when you will give birth. It is calculated by adding 40 weeks (280 days) to the first day of your last period date, but this does not account for women who’s menstrual cycle varies from the norm11. Putting too much focus on your ‘due date’ may make the end of pregnancy quite stressful; it may be better to focus on the whole period between 37-41 weeks11.

A main indicator of your baby’s wellbeing is to monitor their pattern of movements. Movements are usually first noted between 18-24 weeks12, maybe a little earlier if it isn’t your first baby. It is not true that babies move less towards the end of pregnancy and you should continue to feel baby move right up until and during labour12. If you are concerned in any way about your baby’s movements, contact your maternity unit immediately.

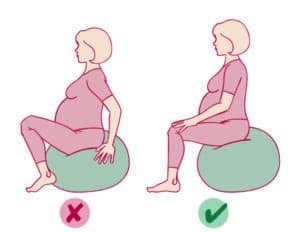

Exercise and remaining active is beneficial to the mother and the baby right up until the end of pregnancy, where comfortable13. In fact, doing moderate exercise is actually recommended. Pregnancy is not the time to start a new fitness regime, but activities such as walking, yoga, pilates and swimming are proven to help lower blood pressure, reduce risk of developing gestational diabetes, improve metabolism, aid lower back pain and improve quality of sleep14. Exercise, keeping upright and active as well as the use of a birthing ball in later stages of pregnancy can help baby into an optimum position for labour and delivery15. [Image 216]

Image 2

What we don’t know

Over the years, there has been a lot of research as to why we go into labour, but the reason remains largely unknown17. There are various theories that suggest triggers for labour may include inflammatory, hormonal, mechanical and even psychological factors, but there is no concrete evidence either way18. However, one thing that is guaranteed is that no one stays pregnant forever!

As a pregnancy is nearing or has passed the due date, women often ask how they can bring on labour without requiring a medical induction. There are many methods that women have reportedly used to start labour; often these suggestions are passed between friendship groups or families and usually have very little evidence to back them up19,20. The NICE (National Institute for Clinical Excellence) Guidelines, to which all NHS trusts in this country should adhere, states that health professionals should advise women that there is no evidence to support the use of herbal supplements, holistic therapies, enemas or sexual intercourse20 to induce labour. There are some methods used to induce labour that can actually be harmful, so always discuss with your care provider before seeking methods to bring on labour. If induction of labour is indicated for medical reasons or in the case of prolonged pregnancy as per the guidelines, this will be discussed with your care provider and a plan will be implemented as required.

Mothers and families: how to use the evidence

- Try not to put all your expectations into the one ‘due date’. This will possibly cause more stress and it is not likely that you will deliver your baby on this day. Instead, expect that you will have your baby somewhere in the 37-42 week window

- Make sure that you and your birth partner are aware of when to call your care provider if you think that labour has started

- Monitor the pattern of your baby’s movements from about 24 weeks. If you notice any change in this, or notice an absence of movements, you must call your care provider immediately. This is applicable right until the end of your pregnancy – baby’s movements will not lessen or decrease just because you are nearing labour.

- Although we don’t know why we go into labour, most babies are born when they are ready18. You may come across many suggestions for bringing on labour yourself, but it is important to do your research and fully discuss any options with your midwife

Midwives and birth workers: how to use the evidence

- As birth workers, the due date is often central to the care we provide to women and their families. We schedule appointments and plan care entirely based around estimated date of delivery. As our work is governed by policy and guidelines that are created to safeguard the mum and the baby, the due date remains important. However, it is essential that we offer evidence-based information to women21 to ensure that they can make truly informed decisions about their care.

- Women in our care may become frustrated that labour has not occurred by the due date and may seek advice on how to bring on their labour. Again, it is essential that we are familiar with the guidelines20,21 and can provide support during this potentially stressful time.

- Providing women and their birth partners with education and reassurance throughout the antenatal period is key to reducing the anxiety that a woman may feel around her due date22 or about her pregnancy in general.

Links to other resources

Social media

Social media

@thepositivebirthcompany

@birth_ed

Guidelines

Guidelines

NICE Guidelines CG70 – Inducing Labour (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/chapter/1-Guidance#methods-that-are-not-recommended-for-induction-of-labour)

Better Births – Improving outcomes of maternity services in England National Maternity Review (https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf)

References

- Speller J (2020) Labour. Teach Me Physiology [Online] Available at: https://teachmephysiology.com/reproductive-system/pregnancy/labour/ (Accessed Oct 2020)

- NHS England (2020) What Happens During Labour and Birth [Online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/what-happens-during-labour-and-birth/ (Accessed Oct 2020)

- McEvoy A, Sabir S (2020) Physiology, Pregnancy Contractions. StatPearls [Online] StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532927/ (Accessed Oct 2020)

- McCormick C (2003) “The First Stage of Labour: Physiology and Early Care” in Myles Text Book For Midwives. 14th edition. Churchill Livingstone: London

- Raines DA, Cooper DB (2020) Braxton Hicks Contractions. StatPearls [Online] StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470546/ (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Becher N, Adams-Waldorf K, Hein M, Uldbjerg N (2010) “The cervical mucus plug: Structured review of the literature” in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Vol 8(5) [Online] Available at: https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1080/00016340902852898 (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Coad J, Pedley K, Dunstall M [Eds.] (2020) Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives. 4th edition. Elsevier LTD: London

- Mongelli M (2016) “Evaluation of gestation” in Medscape [Online] Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/259269-overview medscape.com (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2019) Births by Gestational Age at Birth, England and Wales, 2018 [Online] ons.gov.uk (Accessed Oct 2020)

- NHS England (2018) “You and your baby at 40 weeks pregnant” NHS Choices [Online] Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/40-weeks-pregnant/(Accessed Oct 2020)

- Higson N (2020) “How accurate is my due date?” [Online] Available at: https://www.aims.org.uk/information/item/due-date (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Tommy’s [Online] Available at: https://www.tommys.org/pregnancy/symptom-checker/baby-fetal-movements (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Department of Health (2017) “Physical activity for pregnant women” Department of Health [Online] Available at : https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_datafile/622335/CMO_physical_activity_pregnant_women_infographic.pdf (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Harding M (2017) “Pregnancy and physical activity” Patient [Online] Available at: http://www.patient.info/health/diet-and-lifestyle-during-pregnancy/pregnancy-and-physical-activity (Accessed Oct 2020)

- NCT (2018) “Tips: How to get your back-to-back baby into position for birth” [Online] Available at: https://www.nct.org.uk/labour-birth/getting-ready-for-birth/tips-how-get-your-back-back-baby-position-for-birth (Accessed Oct 2020)

- HSE (2018) Birthing balls and other equipment for labour [Image] [Online] Available at: https://www2.hse.ie/wellbeing/child-health/birthing-balls-and-other-equipment-for-labour.html (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Kamel RM (2010) “The Onset of Human Parturition” in Archives of Gynecology and Obstet Vol 281(6) pp. 975-982 [Online] Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20127346/ (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Hundley V, Downe S, Buckley SJ (2020) “The Initiation of Labour at Term Gestation: Physiology and Practice Implications” in Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Vol 67, pp. 4-18. [Online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S152169342030033X (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Kozhimannil KB et al. (2013) “Use of non-medical methods of labor induction and pain management among U.S. women” in Birth. Vol 40(4) [Online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3868990/ (Accesed Oct 2020)

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Induction of Labour – Clinical Guideline 70 [Online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg70/chapter/1-Guidance#methods-that-are-not-recommended-for-induction-of-labour (Accessed Oct 2020)

- Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Standards for Competence for registered midwives [Online] Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards/nmc-standards-for-competence-for-registered-midwives.pdf (Accessed Oct 2020)

- NHS England (2016) Better Births – Improving outcomes of maternity services in England National Maternity Review [Online] Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf (Accessed Oct 2020)