What Is A Placenta And How Is It Supposed To Come Out?

Mireia Manzano

Staff Nurse and Student Midwife

Every person who grows a baby, grows a placenta too. However, this tends to go highly unrecognised in the birthing world. Sometimes named as “the afterthought”, placentas are organs within themselves, made for the specific purpose of nourishing the baby inside the womb and protecting it from the invasion of potentially harmful substances. At the same time, they secrete multiple hormones that will ensure the sustenance of the pregnancy. These same hormones can also be responsible for some unwanted complications such as gestational diabetes or sickness.3 Following the principles of body autonomy, women have a right to choose how they would like to birth their baby. In the same way, it is up to them to choose how they want to birth their placentas.

The development of the placenta as an independent organ starts from the moment of implantation on the uterine wall. What is particular about placentas is that they receive a dual blood supply: on one face, they are bathed by maternal blood, on the other one they receive blood from the baby via the umbilical arteries. This mechanism is carefully developed to act like a barrier, avoiding the mingling of the two types of bloods. That stops the maternal immune system from developing antibodies against the baby and generating a rejection response.4

After the baby is born, though, the placenta needs to come out. If a physiological method is employed, it is all about waiting. Having the baby suckling at the breast, straight after delivery, will induce another rush of oxytocin (same hormone that stimulates frequent uterine contractions during labour) to generate a powerful shortening of the muscular fibres of the womb. This results in a detachment of the placenta and its subsequent delivery, followed by a certain amount of blood. Women are encouraged to stay upright and keep pushing when they feel contractions. The fast-shrinking uterus is meant to occlude blood vessels and stop mum from haemorrhaging vaginally. Also, if the cord is clamped and cut only after it has stopped pulsating, all the blood retained within the placenta is likely to go into the baby, reducing the amount of blood loss from the maternal side.2 Overall, the whole process can take up to an hour, and is strictly “hands off” on the staff’s side. So, overall, to prevent a substantial haemorrhage after the birth, we need a healthy uterus that is strong and sensitive to natural oxytocin. That is what makes it able to contract to stop the bleeding. And, preferably, an intact cord that can drain blood from placenta to baby before being severed.

Modern obstetrics brought the invention of artificial oxytocin, which is the drug of election when trying to induce labour medically. In the same way it kickstarts contractions in women that are not yet in labour, it can generate the desired contractions that will result in the detachment and expulsion of the placenta. After the baby is born, this “fake” oxytocin can be administered as an injection into the woman’s arm or thigh. A practitioner clamps and cuts the cord, and exerts some traction on it, gently pulling it out of the body. After the injection, the placenta is meant to come out within thirty minutes. If it does not a manual removal of the placenta may be advised, which is done in theatre by doctors under regional anaesthesia. If the placenta is delivered incomplete or with ragged membranes investigations will be started to make sure that there are no pieces of placenta left behind or still attached to the uterine wall, which could increase the chance of bleeding more than normal.2

Nowadays, guidelines encourage all birth workers to offer the injection and controlled cord traction to women, since statistics show that this reduces the chance of having a postpartum bleed.7 That is especially true for women at a higher risk of bleeding, such as twin or triplet pregnancies (the overstretched uterus might struggle a bit more to contract) and induced labours (the body is less responsive to natural oxytocin if it has been receiving the artificial one for a while). However, there are also side effects to it. Nausea and vomiting can be triggered by the injection.6 Controlled cord traction can be felt as unpleasantly invasive. Also, if there is no concern about baby’s health, research has shown that delayed cord clamping is linked to higher iron stores for the infant, as they are more likely to start in life with a full blood supply.1

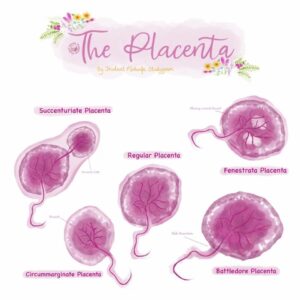

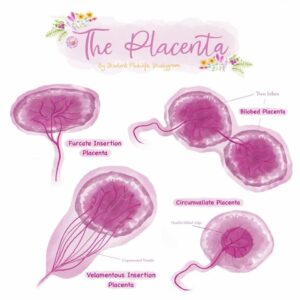

Credit : Instagram @student_midwife_studygram www.studentmidwifestudygram.co.uk

Summary

This general worry to prevent scary bleedings has somewhat forgotten that it is still possible to deliver the placenta in a physiological way, especially for people with no previous conditions and who have enjoyed healthy, uncomplicated pregnancies. Some women might choose to have an undisturbed labour, with as few external interventions as possible. And others might not want artificial oxytocin to interfere with their own natural hormones, which have been proved to be essential for the natural unfolding of labour and the establishing of breastfeeding.5 Facts such as skin-to skin immediately after birth, nipple stimulation (either by the baby or by the partner), adopting postures that aid gravity, or something as simple as being in a comfortable, low-stress environment will trigger this much needed oxytocin for the body to deliver the placenta and stop the bleeding by its own means. It is perfectly acceptable to remind all of this to the professional attending the birth. It is also up to the woman to choose when to cut the cord, as well as the person to do it (husband, partner, etc.). Physiological management is normally practised in homebirths or birth centres, in which a lot of effort goes into promoting a calm, welcoming atmosphere. This is not often the case in crowded labour rooms, with bright lights and high-tech monitors, or where maternal positioning tends to be horizontal in bed for practitioner’s comfort. It is also important to notice that these two ways are not exclusive. If the placenta is not coming out in a physiological manner, if bleeding is concerning or if mum is no longer comfortable with waiting, switching to “injection and cord traction mode” is also a possibility that can be requested to midwives or doctors attending the birth.

Links to resources

Books

Books

Birthing Your Placenta: The Third Stage Of Labour by Nadine Edwards and Sara Wickham

Articles

Articles

Delaying cord clamping is linked to improvements in fine motor skills | The BMJ https://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h2828

Placenta: The Forgotten Organ | Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology (annualreviews.org) https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125620

References

- Wise J. Delaying cord clamping is linked to improvements in fine motor skills. BMJ. 2015; 350.

- Edwards N, Wickham S. Birthing your placenta: the third stage of labour. Edinburgh: Birthmoon Creations: 2018.

- Magill Cuerden J, Macdonald S. Mayes’ Midwifery. Edinburgh: Bailliere Tindall: 2018.

- Maltepe E, Fisher S. Placenta: The forgotten organ. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2015; 31:523-552.

- Wiessinger D, West D, Pitman T. The womanly art of breastfeeding. Cornwall: Pinter&Martin: 2010.

- OXYTOCIN | Drug | BNF content published by NICE

- Recommendations | Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies | Guidance | NICE