The Marvel of Motherhood: Unveiling the Anatomy and Physiology of Spontaneous Labour Onset

Abbie Tomson

Midwife MSc, BSc, Yoga Teacher, Project Lead at All4Birth

@enevlorel

The onset of spontaneous labour is a momentous event, signalling the beginning of a transformative journey into motherhood. Understanding the intricate dance of anatomy and physiology during this natural process is crucial for expectant parents. As pregnancy nears its conclusion, a carefully choreographed interplay of maternal hormones interacts with various physiological processes within the maternal body, uterus, and placenta to prepare for the miraculous event of childbirth. In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the intricate anatomy and physiology underlying maternal hormonal dynamics and their profound influence on the initiation and progression of spontaneous labour.

Through this exploration, we aim to unravel the multifaceted role of maternal hormones in the initiation and progression of spontaneous labour, shedding light on the complex biological mechanisms that culminate in the miracle of childbirth. Join us as we embark on a journey into the fascinating realm of maternal hormonal dynamics and their profound impact on the miracle of life.

Important to note: labour is a natural bodily function and will start when the hormonal changes have occurred and these cannot be forced in healthy pregnancies.

The Role of Maternal Hormones

Maternal hormones play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of spontaneous labour. These hormones interact with various physiological processes within the maternal body, the uterus, and the placenta to prepare for childbirth. Here’s an explanation of the anatomy and physiology behind how maternal hormones can lead to the onset of spontaneous labour:

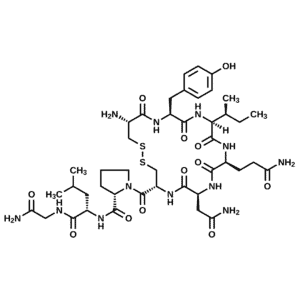

1. Oxytocin:

– Oxytocin is often referred to as the “love hormone” or “bonding hormone,” but it also plays a central role in labour.

– During pregnancy, oxytocin receptors increase in number and sensitivity in the uterine muscle (myometrium) and the cervix.

– As labour approaches, maternal oxytocin levels rise, stimulating uterine contractions. These contractions gradually increase in intensity and frequency, leading to the dilation and effacement of the cervix and the eventual birth of the baby.

– Oxytocin is released in response to various stimuli, including nipple stimulation, cervical stretching, and pressure on the uterus from the growing fetus. Oxytocin increases as Braxton Hicks continue to become more frequent. However…oxytocin receptors are made in the layers of the uterus wall- labour won’t start without oxytocin receptors! But Braxton Hicks help these increase in the uterus wall.

2. Oestrogen:

– Oestrogen levels rise significantly during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester.

– Oestrogen plays a crucial role in preparing the uterus for labour by promoting uterine muscle contractility and increasing the number of oxytocin receptors on uterine muscle cells.

– Oestrogen also contributes to the softening and ripening of the cervix by stimulating the production of enzymes that break down collagen fibres in the cervical tissue, allowing for cervical dilation and effacement.

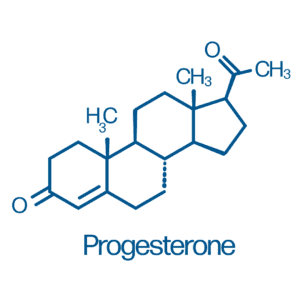

3. Progesterone:

– Progesterone levels remain high throughout most of pregnancy and help maintain uterine quiescence (relaxation) to prevent premature contractions.

– Progesterone supports blood flow to the cervix to aid it in effacing (thinning and shortening)

4. Prostaglandins:

– Prostaglandins are lipid compounds produced by various tissues, including the uterine lining (endometrium) and fetal membranes.

– Maternal prostaglandins play a crucial role in cervical ripening and the initiation of labour. They help soften and dilate the cervix, making it more favourable for childbirth.

– Prostaglandins also stimulate uterine contractions directly and enhance the effects of oxytocin on uterine muscle cells.

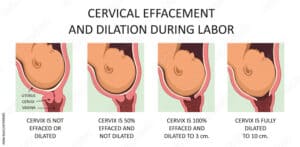

Cervical Changes

The cervix, the lower part of the uterus that connects to the vagina, undergoes significant changes during pregnancy and labour. These changes are crucial for the onset and progression of spontaneous labour. Understanding the anatomy and physiology behind cervical changes can provide insights into how labour is initiated. Here’s an overview:

1. Cervical Softening (Ripening):

– Anatomy: The cervix normally remains firm during most of the pregnancy due to the presence of collagen fibres in its connective tissue. However, as labour approaches, the cervix undergoes a process called ripening or softening.

– Physiology: Ripening of the cervix involves a breakdown of collagen and an increase in water content, leading to increased pliability and softness. This process is primarily mediated by prostaglandins, which stimulate the production of enzymes that degrade collagen fibres in the cervix. As a result, the cervix becomes softer and more stretchable, preparing it for dilation during labour.

2. Cervical Dilation:

– Anatomy: Cervical dilation refers to the opening or widening of the cervix to allow the passage of the baby through the birth canal. The cervix is normally closed tightly during pregnancy to protect the developing fetus.

– Physiology: Dilation of the cervix is a coordinated process involving both mechanical stretching and biochemical changes. Prostaglandins, along with other hormones like estrogen, play a crucial role in promoting cervical dilation by stimulating the relaxation of smooth muscle cells in the cervix. Additionally, oxytocin, released in increasing amounts during labour, enhances the strength and frequency of uterine contractions, which exert pressure on the cervix, further promoting dilation.

3. Cervical Effacement:

– Anatomy: Cervical effacement refers to the thinning and shortening of the cervix that occurs as labour progresses. This allows the cervix to be drawn up into the lower uterine segment, facilitating the passage of the baby through the birth canal.

– Physiology: Effacement is closely linked to cervical dilation and is often described in terms of a percentage (e.g., 50% effaced). As the cervix dilates, it also undergoes effacement. Prostaglandins and estrogen contribute to cervical effacement by promoting the softening and remodelling of cervical tissue, allowing it to thin out as labour progresses.

4. Cervical Changes in Response to Hormones:

– Anatomy and Physiology: Hormones such as oestrogen, progesterone, prostaglandins, and oxytocin play key roles in regulating cervical changes during pregnancy and labour. Oestrogen, for example, increases the production of cervical mucus, which helps to seal the cervix during pregnancy but becomes more fluid as labour approaches. Prostaglandins stimulate cervical ripening and dilation, while oxytocin enhances uterine contractions that contribute to cervical effacement and dilation.

Uterine Contractions

The onset of spontaneous labour involves complex changes in the uterus, particularly in the cervix and uterine muscle, which are crucial for the initiation and progression of labour. Here’s an explanation of the anatomy and physiology behind how uterine contractions can lead to the onset of spontaneous labour:

1. Anatomy of the Uterus:

– The uterus is a muscular organ located in the pelvic cavity.

– It consists of three layers: the outermost serous layer (perimetrium), the middle muscular layer (myometrium), and the inner mucous layer (endometrium).

– During pregnancy, the myometrium undergoes significant changes, including hypertrophy (enlargement) and increased contractile activity.

2. Physiology of Uterine Contractions:

– Uterine contractions are coordinated, rhythmic muscular movements of the myometrium.

– These contractions are initiated and regulated by the interplay of various hormones, including oxytocin, prostaglandins, oestrogen, and progesterone, as mentioned in the previous response.

– Oxytocin, released in increasing amounts during labour, stimulates uterine contractions by binding to oxytocin receptors on uterine muscle cells. This leads to the activation of intracellular signalling pathways that result in uterine muscle contraction.

– Prostaglandins play a role in enhancing the sensitivity of uterine muscle cells to oxytocin and promoting the initiation of contractions.

– Oestrogen contributes to the synthesis of oxytocin receptors on uterine muscle cells, thereby increasing the responsiveness of the uterus to oxytocin.

– The decline in progesterone levels removes its inhibitory effect on uterine contractility, allowing contractions to occur.

3. Effects of Uterine Contractions:

– Uterine contractions serve multiple functions during labour:

– Cervical effacement and dilation: Contractions exert pressure on the cervix, causing it to thin (efface) and dilate. This process is crucial for allowing the baby to pass through the birth canal.

– Fetal descent: As the uterine contractions intensify, they push the fetus downward, aiding in its descent through the birth canal.

– Rupture of membranes: Strong uterine contractions may lead to the rupture of the amniotic sac, resulting in the release of amniotic fluid (commonly referred to as the “breaking of water”).

4. Positive Feedback Loop:

– Uterine contractions often operate in a positive feedback loop during labour. As contractions occur, they stimulate the release of more oxytocin, which leads to stronger contractions, further promoting cervical dilation and fetal descent.

Fetal Positioning

Fetal positioning refers to the orientation and presentation of the fetus within the uterus, particularly with the birth canal. The anatomy and physiology behind how fetal positioning can lead to the onset of spontaneous labour involve various factors, including the pressure exerted by the fetal head or body on the cervix and surrounding structures. Here’s an explanation:

1. Fetal Engagement:

– Before labour begins, the fetus typically undergoes a process called engagement or descent, where the fetal head (or presenting part) descends into the maternal pelvis.

– Engagement occurs when the widest diameter of the fetal head passes through the pelvic inlet. This places pressure on the cervix, contributing to cervical effacement (thinning) and dilation.

2. Mechanical Pressure:

– The pressure exerted by the fetal head on the cervix during engagement stimulates the release of hormones such as oxytocin and prostaglandins, which are involved in initiating and promoting labour.

– As the fetal head presses against the cervix, it can also stimulate nerve endings in the cervix, leading to the release of oxytocin and other signalling molecules that further stimulate uterine contractions.

3. Fetal Position:

– The position of the fetus within the uterus can also influence the onset of spontaneous labour.

– For example, an optimal fetal position for labour is the cephalic presentation, where the baby’s head is down and facing the mother’s back. This position allows for the most efficient passage through the birth canal.

– In contrast, deviations in fetal positioning, such as breech presentation, may lead to delays or complications in labour initiation..

Fetal Hormones

Fetal hormones play a significant role in the initiation and progression of spontaneous labour, primarily through their interactions with maternal hormonal and physiological systems. While the fetus itself does not produce hormones independently in the same way as adult organisms, it influences maternal hormone levels through various mechanisms. Here’s an explanation of the anatomy and physiology behind how fetal hormones can contribute to the onset of spontaneous labour:

1. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH):

– CRH is produced by the fetal hypothalamus and placenta.

– During late pregnancy, fetal CRH levels rise significantly.

– CRH stimulates the maternal pituitary gland to produce adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn stimulates the maternal adrenal glands to produce cortisol.

– Elevated maternal cortisol levels have been associated with the onset of spontaneous labour. Cortisol plays a role in promoting the synthesis of prostaglandins, which contribute to cervical ripening and uterine contractions.

2. Oestrogen:

– Oestrogen is produced by the fetal adrenal glands, liver, and placenta, with the placenta being the primary source during pregnancy.

– Fetal oestrogen levels rise towards term and peak just before labour.

– Oestrogen contributes to the softening and ripening of the cervix by promoting the synthesis of collagenases and other enzymes that degrade the cervical collagen matrix, leading to cervical dilation.

3. Prostaglandins:

– Prostaglandins are lipid compounds produced by various tissues, including the fetal membranes, placenta, and amniotic fluid.

– Fetal prostaglandins are thought to contribute to the initiation of labour by stimulating uterine contractions and promoting cervical ripening.

– Prostaglandins produced by the fetal membranes may also play a role in the rupture of membranes, leading to the release of amniotic fluid and the onset of labour.

4. Oxytocin:

– While oxytocin is primarily known for its role in labour when produced by the maternal hypothalamus and posterior pituitary gland, it’s worth noting that fetal oxytocin is also present.

– Fetal oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus and can influence the timing of labour through its effects on uterine contractility.

– Oxytocin receptors are present on fetal membranes, and oxytocin released by the fetus may contribute to the stimulation of uterine contractions and the onset of labour.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intricate dance of maternal hormones during pregnancy culminates in the awe-inspiring phenomenon of spontaneous labour, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the journey of motherhood. As we’ve explored the pivotal roles played by oxytocin, estrogen, progesterone, and prostaglandins, it becomes evident that these hormones orchestrate a symphony of physiological changes within the maternal body and uterus, meticulously preparing for the miracle of childbirth.

From the softening and dilation of the cervix to the rhythmic contractions of the uterine muscles, maternal hormones govern every aspect of labour, ensuring the safe delivery of the precious new life. Furthermore, the influence of fetal hormones adds another layer of complexity to this intricate process, underscoring the interconnectedness of maternal-fetal physiology in the initiation and progression of labour.

As we marvel at the intricacies of maternal hormonal dynamics, we gain a deeper appreciation for the wonders of nature and the miraculous journey of birth!

Links to resources

Books and articles

Books and articles

Brain Health from Birth: Nurturing Brain Development During Pregnancy and the First Year by Rebecca Fett

Real Food for Pregnancy by Lily Nichols

Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing: Evidence and Implications for Women, Babies, and Maternity Care

Film Audio and Apps

Film Audio and Apps

Baby Buddy app, created by the Best Beginnings Charity

Websites

Websites

References

- Coad, J. (2019). Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives. Elsevier.

- Marshall, J. E., & Raynor, M. D. (2019). Myles Textbook for Midwives. Elsevier.

- Tossetta G. (2023). Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Placenta. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(10), 9066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24109066

- Pascual ZN, Langaker MD. Physiology, Pregnancy. [Updated 2023 May 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559304.

- Hundley V, Downe S, Buckley SJ (2020) “The Initiation of Labour at Term Gestation: Physiology and Practice Implications” in Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Vol 67, pp. 4-18. [Online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S152169342030033X (Accessed March 2024)